The Times Building and the 1911 Telegram

The Times Building and the 1911 Telegram

The Times Building in New York, completed in 1904, became the new headquarters of The New York Times. The paper gave the square its name when it moved there from Park Row. Later, the building became famous for the electric news “zipper” sign that wrapped around its façade.

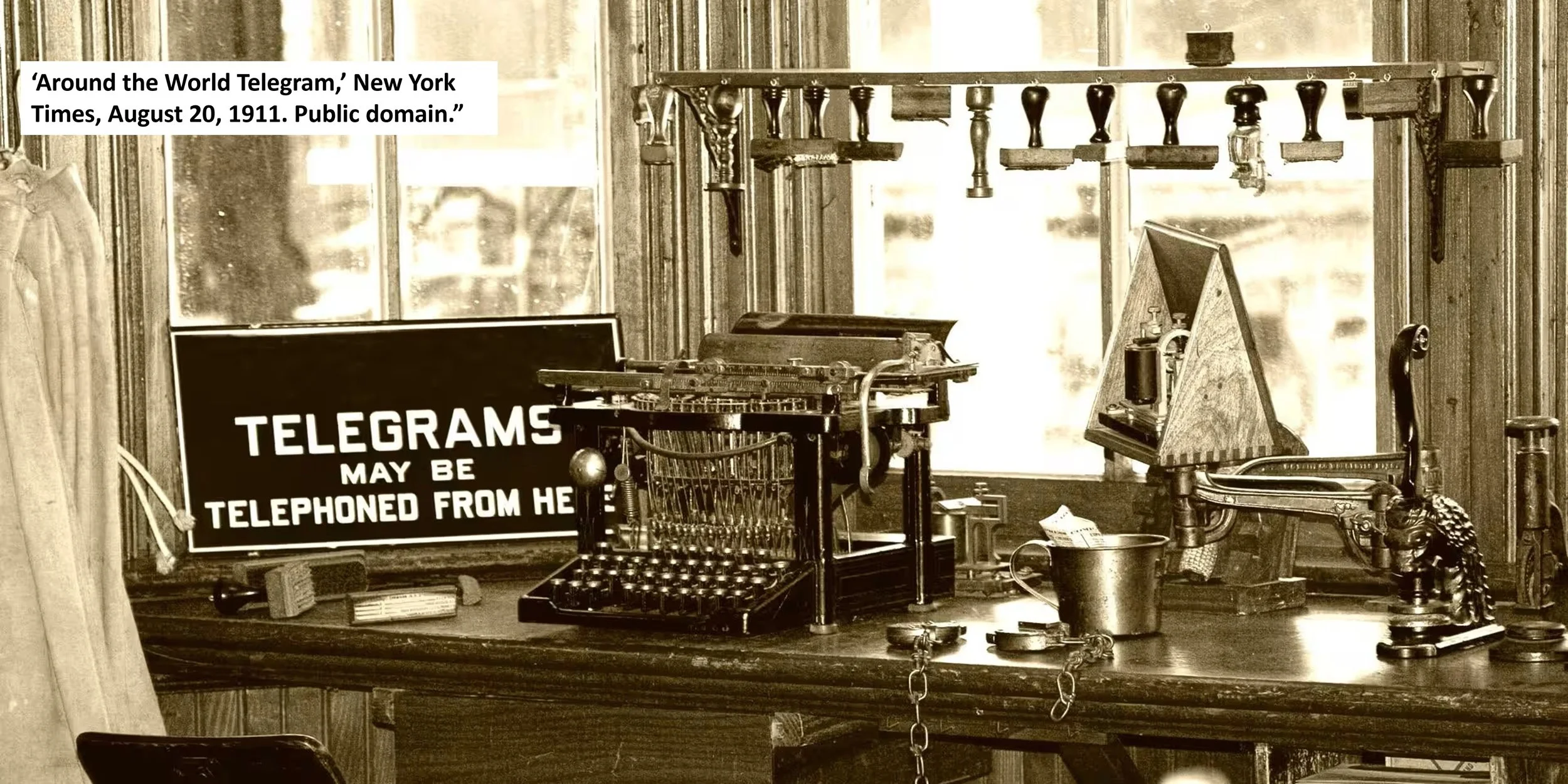

The Western Union Telegraph Company, meanwhile, operated its main headquarters at 195 Broadway, farther downtown. However, Western Union maintained telegraph rooms within major newspapers, including The Times. These rooms were fully equipped with Western Union instruments and staffed by operators, all of whom were connected directly into Western Union’s nationwide network.

On August 20, 1911, the Times used its own telegraph room—located on the second floor of the Times Building—to send the famous “Around the World Telegram.” At 7:00 p.m., an operator tapped out the test message: “This message sent around the world.”

The signal raced across the Atlantic to Europe, through Asia, across the Pacific, and back to New York. In only 16 and a half minutes, the telegram returned to the same office—proof that news could now circle the globe almost instantly.

✨ Awe and Wonder: In a modest second-floor room, surrounded by clacking telegraph sounders, a few taps on a key shrank the world. For the first time, humanity had seen the planet tied together by a web of wires.

Around the World Telegram

Scale of Control

By the early 20th century, Western Union operated more than 20,000 telegraph offices and controlled about 90% of the telegraph lines in the country. It had absorbed or outcompeted most rivals, including the American Telegraph Company, the United States Telegraph Company, and numerous local lines.

Why It Was a Monopoly

Network dominance: Telegraph lines were expensive to build and maintain. Once Western Union strung wires along the main railroads and created a nationwide system, it became almost impossible for competitors to match the reach.

Mergers and acquisitions: Western Union bought out smaller companies, consolidating nearly all independent operations.

Exclusive agreements: They secured contracts with railroads to run telegraph lines along rights-of-way, shutting competitors out of the most efficient routes.

Competition Attempts

There were occasional challengers—such as Postal Telegraph Company—but they remained secondary players. Postal Telegraph survived, but its network was a fraction of Western Union’s and usually charged higher rates.

Awe and Wonder Moment

Imagine walking into almost any town in America in 1905. If you wanted to send a message across the country in minutes, instead of days by train, you would almost certainly step into a Western Union office. That single company became the nervous system of America’s communication network, transmitting millions of messages each year. In many ways, it was the “internet provider” of its day.

Radio Waves Coming from Space

Where does light come from? Your first thought is probably the Sun—and you’re right. But what about at night? You might say the Moon, yet the Moon does not create its own light. It simply reflects sunlight. That leaves the stars as our true nighttime source of light. Each star is part of a galaxy, like the one shown in this image, so when you see the night sky twinkle, you are really looking at galaxies across space.

Scientists call light electromagnetic radiation (EMR), a term that comes from the work of James Clerk Maxwell, a Scottish physicist. The name combines electricity and magnetism because all EMR begins with moving electrons that create magnetism. Light is just one type of EMR. The rainbow colors we see with our eyes make up only a tiny fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum, shown here as the purple bar beneath the galaxy.

A light wave has two features: its length and its up-and-down oscillation, like the wiggles drawn coming out of the galaxy. The distance from one wave top to the next is its wavelength. Different types of light have different wavelengths, and their sizes can be compared to everyday objects—mountains for radio waves, bacteria for ultraviolet light, and atoms for X-rays. Beyond visible light, galaxies also shine in the infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray, and even gamma-ray ranges.

The most astonishing fact is this: long before humans built radios, the only radio waves on Earth came from distant galaxies. Today, we add to that cosmic chorus with our own man-made EMR—broadcasting music, phone calls, and data across the planet.

Wireless Digital Communication Pioneers

Intro

Today we live in the age of wireless communication — cellphones, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth connect us instantly. But this power was built step by step, through the work of a few daring pioneers.

Morse & Vail

In 1837, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail created the telegraph and Morse code, the first digital language. In 1851, at the Paris Telegraph Conference, nations adopted Morse code as the world’s standard.

Edison

In 1869, Thomas Edison advanced telegraphy with the quadruplex system, sending multiple messages at once. His work opened the electrical age of communication.

Hertz

In 1887, Heinrich Hertz proved the existence of radio waves — invisible energy that could leap across space without wires.

Marconi

Building on Hertz’s discovery, Guglielmo Marconi sent the first transatlantic wireless signal in 1901, proving that oceans could no longer block human conversation.

Titanic / SOS

All these discoveries converged in 1906, when the Berlin Conference adopted SOS as the universal distress signal. And in 1912, during the sinking of the Titanic, wireless operators sent SOS across the Atlantic, saving lives and proving the world had entered the age of wireless digital communication.

Closing

The awe is this: four inventors, one international decision, and a single tragic shipwreck created the foundation of the wireless world we depend on today.

Thomas Edison and the Telegraph System

The DIY Student-Made Telegraph Sounder

This hands-on project introduces students to core principles of electromagnetism, magnetic fields, Ohm’s Law, and energy transformation. As current flows through a hand-wound coil, it creates a magnetic field that pulls an armature—converting electrical energy into mechanical motion and audible sound. Students learn how resistance, voltage, and current interact, and how a simple device can encode digital information. Inspired by Edison’s early telegraph inventions, this build links 19th-century ingenuity to modern communication. It transforms abstract equations into observable effects, sparking awe as students hear electricity “speak” for the first time.

Telegraph Sounder

How the Telegraph Sounder Made Sound

This slide shows how the original telegraph sounder worked as a transducer converting electricity into sound waves. When a current flowed through the electromagnet coils, they generated a magnetic field that pulled the iron armature downward. That motion caused the armature to strike the lower contact plate, creating a distinct “click.” When the circuit broke, the current stopped, and the magnetic field collapsed. A spring snapped the armature back up, where it struck the top contact, producing the “clack.” These two mechanical impacts produced short, sharp sounds precise enough for trained operators to distinguish Morse code by ear. Telegraphers listened for the pattern of clicks and clacks to decode dots and dashes. The sounder thus acted as a transducer, transforming silent electrical pulses into mechanical motion and then into audible signals. This auditory channel allowed operators to decode messages in real time, one of the earliest examples of real-time digital communication through sound.

Morse Code: A Brain-Training Legacy

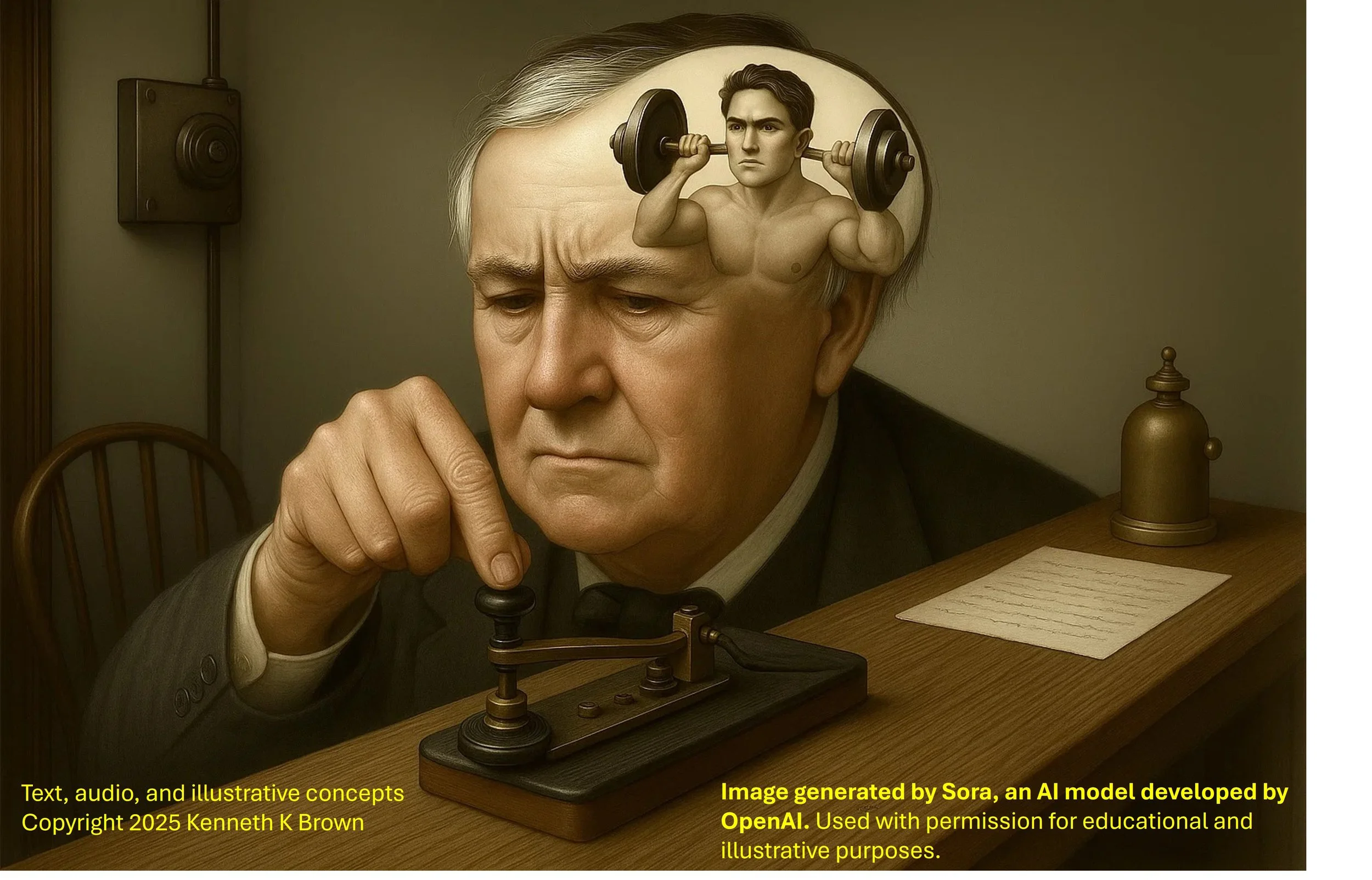

Thomas Edison practising telegraphy,

When Thomas Edison became a teenage telegraph operator, he was unknowingly building more than messages—he was building his brain. Practicing Morse code activates six core mental functions: working memory, attention, pattern recognition, auditory processing, brain plasticity, and mental stimulation.

What makes Morse so powerful is its layered abstraction. It trains the brain to convert sound into symbols, symbols into letters, and letters into meaning, engaging different cognitive systems in a seamless and unified process.

Today, Morse code is more than a historical curiosity. It’s used by amateur radio operators, military specialists, science educators, makers, survivalists, and even Deaf-Blind communicators. Lifelong learners use it to keep their minds sharp, focused, and engaged.

Morse endures because it’s more than a code—it’s a mental gymnasium that challenges and rewards across every age.

Make 6” Clothespin Morse Code Keyer

Creating a DIY Morse-Vail telegraph key using a clothespin offers a hands-on exploration of early telegraphy. However, standard laundry clothespins typically range from 1" to 4" and often lack sufficient stability. The largest available 4" clothespin is challenging to find and does not fully replicate one essential component: the trunnion.

In original Morse-Vail keys, a trunnion—a specialized pivot or ball-bearing mechanism—supports smooth and stable motion of the lever. Regular clothespins lack this trunnion, resulting in less precise lever action. Using a larger 6" decorative clothespin partially addresses this issue. Its larger spring mimics the trunnion's pivot action, improving stability and functionality. Additionally, incorporating a knurled nut machine screw provides precise adjustments for spring tension and the anvil-hammer contact distance.

Thus, while everyday clothespins demonstrate basic telegraph principles, utilizing a larger clothespin and adjustable components significantly enhances realism, precision, and effectiveness in the student version of a Morse code keyer

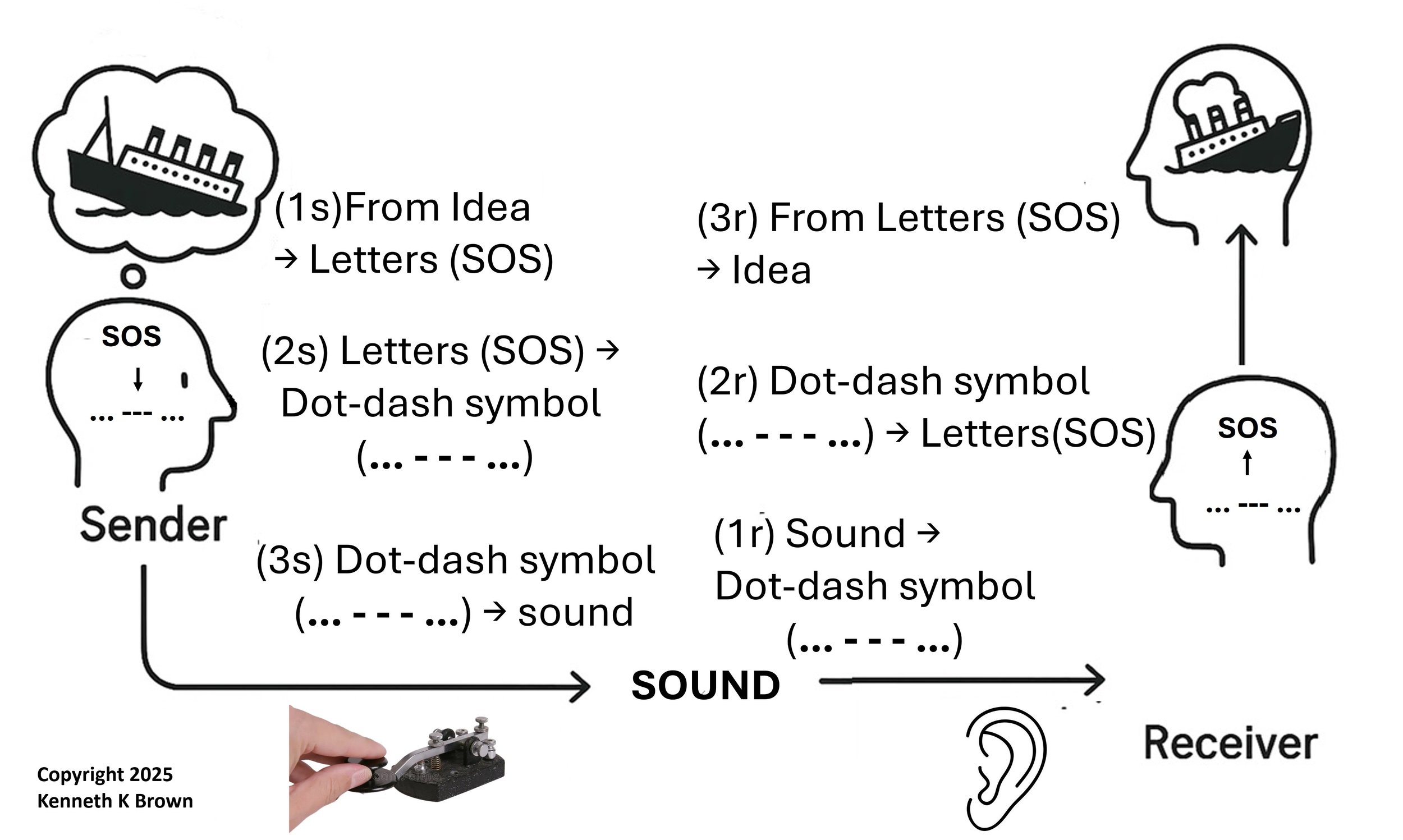

Three Levels of Abstraction in Morse Code Communication

The Three Levels of Abstraction in Morse Code Communication

Morse code turns a thought into sound through three mental steps—each one a level of abstraction. First, the sender uses semantic abstraction to convert an idea into letters (e.g., "The ship is sinking" → "SOS"). Second, symbolic abstraction changes those letters into Morse code symbols ("SOS" → "... ––– ..."). Third, perceptual abstraction transforms the symbols into sound (beeps and dashes using a telegraph key).

The receiver reverses this: first hearing the sound (perceptual), then recognizing the dot-dash symbols (symbolic), and finally understanding the message as a cry for help (semantic).

This process shows how Morse code links sound, symbol, and meaning across minds.

If your ship was sinking—how would you cry for help?

If your ship was sinking, how would you cry for help?

On April 15, 1912, as the Titanic slipped beneath the waves, its operators tapped out three letters that echoed across the Atlantic: S-O-S.

Morse code, developed in the 1830s by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail, uses dots and dashes—short and long signals—to represent letters and numbers. It condensed language into pure pattern, perfect for radio waves and telegraph wires.

Learning Morse code rewires the brain. You hear a sound, convert it to a symbol, then a word, then meaning—three levels of abstraction in seconds. That’s symbolic reasoning in action.

It sharpens memory, builds resilience, and connects you to the early age of global communication.

The message at the end of this clip—“CQ CQ CQ DE KF8BAB”—means: “Calling all stations. This is KF8BAB.”

Student DIY "Make"Clothespin Telegraph Key

This clothespin telegraph key is a student-built model inspired by the original Morse-Vail straight key. It includes the essential components of a real telegraph key: a knob, lever, base, frame, spring, hammer, and anvil. Two special parts—an adjustment screw and a trunnion nail—allow students to fine-tune the tension and pivot, just like the professionals once did. Though made from simple materials, this model performs the same function: pressing the lever completes an electric circuit and produces a clicking sound. Each click can become a dot or dash in Morse code.

Building this device engages more than the hands, it activates memory, reasoning, and curiosity. Students don’t just learn about electricity and communication, they live it. This transforms abstract ideas into something concrete, testable, and unforgettable.

By making something that works, students experience the same thrill of discovery that once connected the world by wire.

The Morse-Vail Telegraph Key: A Classic Design

This image shows the Morse-Vail straight key, the most influential early telegraph design. It has ten essential parts: the knob, lever, frame, and base form the physical structure. The upper and lower contacts—hammer and anvil—complete the circuit when pressed. A spring and two screws adjust contact gap and lever tension. The trunnion screws let the lever pivot, while a return spring resets it. Later models added a shorting switch to reduce noise when idle.

Each press sends a pulse—dot or dash—in Morse code. Invented by Morse in 1837, this key replaced his earlier portarule design. Alfred Vail’s refinements made it practical, robust, and easy to use, launching the telegraph era.

What Hath God Wrought: The Message That Opened the World

Samuel Morse

Before Morse, telegraph systems needed multiple wires—one for each signal—making them costly and impractical. Morse solved this with three breakthroughs. First, he used the Earth as the return path for current, eliminating the need for a second wire. This cut costs and made long-distance telegraphy possible. Second, he invented Morse Code, a simple system of dots and dashes that encoded any message using short and long electrical pulses. Third, he built a reliable electromagnet receiver that clicked or marked each signal as it arrived, allowing operators to “hear” the message. In 1844, Morse sent "What hath God wrought" from Washington to Baltimore over a single copper wire. That moment launched a communication revolution. By combining simplicity, code, and the Earth itself, Morse created a system so scalable that it soon circled the globe—and changed history.

Edison Enters the Book of Real Inventions (1875)

In 1875, when Thomas Edison was just 28 years old, he was invited to write for the Cyclopædia of Applied Mechanics—a massive book filled with real inventions and how they work. Look closely at the image—his name is circled, proof of his place among serious inventors. He was much more than just another businessman. Edison wrote about the telegraph, a machine that sent messages using electricity and clicking sounds.

To be published in this book meant something big: other inventors now trusted Edison’s work. He was no longer just a boy with gadgets—he had become a respected builder of ideas. That reminded me of writing a dissertation. It was a license to practice professionally.

Edison reached this milestone by asking bold questions, testing new ideas, and learning from failure. When one invention failed, he asked, What went wrong?—and tried again. He learned from his mistakes.

This is how science grows—not just from facts, but from awe, wonder, and the thrill of discovering how the world works.

What did you wonder about today?

Edison and the Telegraph: The Spark that Started It All

Before Edison became the Wizard of Menlo Park, he was a teenage telegraph operator. His first scientific breakthroughs weren’t light bulbs or phonographs—they were electric signals pulsing through copper wire. At a wooden desk with a simple key, he sent clicks and pauses that crossed miles in seconds. These invisible pulses revolutionized business, warfare, and everyday life.

n earned 1,093 U.S. patents and over 2,300 worldwide, but his earliest 100 inventions all focused on telegraphy—the first system to conquer time and distance. From that humble beginning, he built the future. In this presentation, we’ll unlock the science of telegraphy by building and testing a working telegraph system— just like Edison did.

.

Heroic Rescue at the Mount Clemens, Michigan, Depot — August 1862

This dramatic act of bravery—Thomas Edison saving Jimmie Mackenzie—marks a pivotal moment that shaped scientific history. At just fifteen, Edison didn’t merely rescue a child; he earned access to a telegraph office and its mysteries. This act of courage became the ignition point for Edison’s lifelong fascination with electrical communication.

Morse code was more than dots and dashes—a language of power, speed, and connection. Under James Mackenzie’s mentorship, Edison didn’t just learn to tap out messages; he learned to think like a signal. It’s awesome how one impulsive moment opened the gateway to an entirely new world of physics and engineering for Tom. What followed was wonderful: Edison’s mastery of the telegraph evolved into inventing the phonograph, refining the light bulb, and birthing the modern electric age.

Heroes Who Lift Students Up

A hero is someone admired for courage, achievement, or noble character. For students, heroes do more than inspire—they lift. They model what is possible and offer a vision of who the student could become.

The image shows this power: a hero carrying a student skyward, symbolizing mentorship, guidance, and vision. In real life, this happens in apprenticeship relationships, where students grow by observing and imitating experts.

Introverted students often first meet heroes through books, movies, or virtual mentors. These heroes become mirrors of possibility—even without personal contact, their values can take root.

But students need help choosing heroes wisely. Parents and teachers must guide them with discernmentso they follow those who stand for resilience, creativity, and truth.

Today, Edison's Experiment Would be a Felony

In the movie Young Tom Edison, he secretly made nitroglycerin to satisfy his scientific curiosity. At fourteen, I followed in his footsteps. I chilled fuming acids… carefully added glycerin drop by drop…and watched golden droplets settle to the bottom… transferred the droplets to the lab bench…and experimented with controlled ignitions and detonations. Then, one drop of the vasodilator touched my skin. My heart raced. My head pounded. I never did that again.

Edison walked away from explosives. He chose discovery over destruction. That choice made him great. Ethical scientists don't just chase power. They learn from their mistakes, and in that way they turn awe into wisdom...and wonder into progress.

Today, Edison's experiment would be a felony under 18 U.S.C. § 842(a)(1) and Ohio Rev. Code § 2923.17. Don’t do this experiment at home.